Burn your TV in your yard

And gather 'round it with your friends

And warm your hands upon the fire

And start again

Take the story you've been sold

The lies that justify the pain

The guilt that weighs upon your soul

And

throw 'em all away

People keep

asking why I am still here. Ebola is gone. Come home. The TV news said there

haven’t been any Ebola cases for weeks. The disease is defeated. The enemy

vanquished. Happy Christmas, War is Over was I think how John Lennon put it.

Victory. None of this is true. Burn your TV.

There was a

positive case just yesterday here in Monrovia. He died. During the last few

days of his life he was not recognized as an Ebola patient and came in contact

with hundreds of people in the community to include many healthcare workers.

The good news is no one has since popped up as positive from this event – yet –

and the system the government and partners have put in place to find people

that may have been exposed is working well. The process is called contact

tracing and it is perhaps the single most essential part of defeating this

disease. What it means is you have to find every single person that may have

been exposed to the infected person and at a minimum follow them on a daily

basis for the proverbial 21 days. In some cases, depending on the potential

severity of the exposure you may physically quarantine them. The teams here are

now quite skilled at contact tracing. And it works. When you so closely monitor

potential patients and isolate them the minute they start to appear ill it

markedly decreases the chance they will continue to pass along the infection.

All the virus wants to do is propagate, build a chain link by link. Contact

tracing stops the next link from even being built. Think of how many people you

come into contact with every day in your routine. Hundreds? Thousands?

Let’s explore the

word quarantine for a minute. We all know what it means. We hear it used on the

TV news, read about it in the papers but where does it come from? The word

"quarantine" originates from the Venetian dialect form of the Italian

quaranta giorni, meaning 'forty days'. This is due to the 40-day

isolation of ships and people before entering the city of Dubrovnik in Croatia.

This was a measure of disease prevention related to Black Death. Between 1348

and 1359, the Black Death wiped out an estimated 30% of Europe's population,

and a significant percentage of Asia's population. Just to refresh your memory,

the Black Plague was caused by bacteria that used fleas and rats as part of its

transmission cycle. Not nearly as exotic as Ebola which is a filovirus and

probably carried by bats but just as deadly back then. I have to remind you of

another part of the Black Plague’s history that you may not know. We are all

familiar with the children’s rhyme ring around the rosie, pocket full of posies,

ashes ashes we all fall down but we may not be aware that is all about the

Plague. The ring referred to a classic skin sign of infection, the pocket full

of posies was carried to mitigate the stench of death and the ashes and falling

down referred to the deaths. I am not sure if Ebola will birth its own nursery

rhymes. We’ll see.

The

original quarantine document from 1377 is kept in the Archives of Dubrovnik and

states that before entering the city newcomers had to spend 30 days -a trentine

- in a restricted place waiting to see whether the symptoms of Black Death would

develop. Later, isolation was prolonged to 40 days and called quarantine. Venice took the lead in measures

to check the spread of plague and appointed three guardians of public health in

the first years of the Black Death (1348). They enforced quarantine on ships at

harbor and even built quarantine facilities on small islands. Venice – such a

great city.

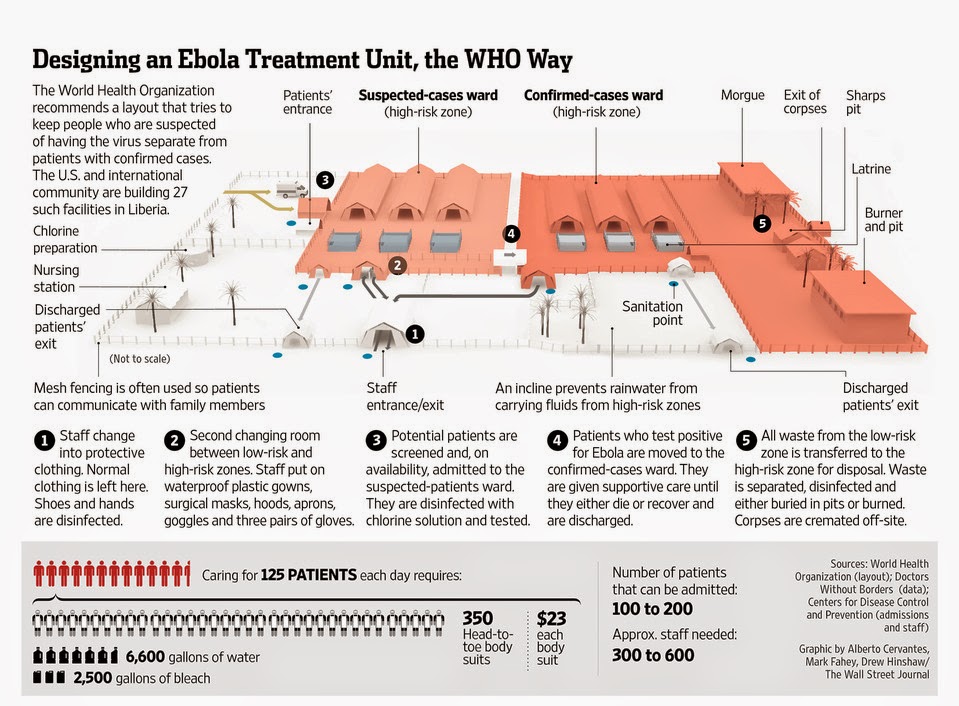

So

what happens when somebody gets Ebola? I’ll save the clinical talk for a different

time but let me walk you through how a patient is cared for. There are of

course many schools of thought - doctors are even worse than lawyers when it

comes to arguing - but there are established protocols that most agree on. A

patient showing symptoms gets to care sites in many different ways. If a person

is laying on the floor of their house or hut showing symptoms people know now

to contact the authorities. A specially trained and outfitted team and

ambulance goes and gets the patient. They know to bring them to an Ebola

Treatment Unit – an ETU. Patients may also show up on foot, via motorcycle or

even via wheelbarrow.

Once

at the ETU the patient begins to follow a very prescribed path that seeks to

isolate and protect the patient and protect the staff. The first part is

triage. There, across at least a meter or two of barrier separation, a quick

history is taken. The patients are guided on taking their own temperature with

an accurate digital thermometer. A judgment call is made right there whether or

not the patient fits the criteria. If so, a team in PPE (the spacesuits) comes

and escorts the patient into an area where they are cleaned and their

belongings gathered. They are now brought to a ward called the suspect ward.

Here they have a blood test drawn and samples are sent. The patient receives

what is called presumptive care at this point. Presumptive just means you

assume that everyone may also have malaria and infectious diarrhea – both very

common – and while you are waiting for the test to come back you may as well

treat these. Supportive care like nutrition and fluids are also given and of

course symptomatic care is given for fevers, pain and nausea for example.

It

may take a day or two for a test to come back. If it is positive the person is

moved to a completely new ward called the confirmed ward. Additional testing

takes place. More aggressive treatment continues. The same categories of care –

presumptive, supportive and symptomatic remain. Remember – there is no cure or

vaccine for Ebola – yet. There are very strict guidelines on how patients and

staff move and travel through the facility. One rule is there is no

backtracking. A patient will never go back to the suspect area once confirmed.

Remember some there in the suspect area may not have the disease. Likewise, a

staff member always travels from suspect to less infectious to most infectious

and does not backtrack either in order to minimize the chance of infecting

other patients. The whole patient and staff flow is exquisitely choreographed.

Those who went before us taught us.

Once

in the confirmed ward there are two possible patient outcomes. The patient

either survives and recovers or succumbs to the disease. If they recover there

is a protocol for confirming a disease free state and the patient is released.

They exit through a special area called Freedom’s Gate by some. They are given

the appropriate support to include the basics like bedding, clothing and food

since most everything was destroyed on arrival. No one is just sent out the

door. The communities have a well-established network of support facilities and

services. Still, a stigma surrounds Ebola survivors and many find it rough

going. It is not unlike that experienced by HIV patients back in the day.

Goodness, I just thought about my early days taking care of HIV/AIDS patients

back at San Francisco General in the early 80’s. It wasn’t even called AIDS. We

called it Gay Lymph Node Disease or Gay Related Immune Deficiency (GRID). We

were all so naïve but terrified. Again, the similarities are striking.

Many

patients die. Fatality rates range from 20-95% for Ebola. With good care in an

ETU setting the more favorable numbers play out. When a patient does die they

are treated with the utmost respect but again with very established protocols

for the handling of remains. A recently deceased body is highly highly

infectious. The ETUs all have proper morgues and a way to handle the remains. A

very special NGO called Global Communities has taken the lead throughout this

crisis for handling and burying remains. The ETUs transfer the deceased – again

protocols – to the Global Communities personnel who transport the patient for

burial. Every effort is made to include families in the process with appropriate

attention to infection control.

I

neglected to mention what happens to those in the suspect ward who prove

negative. Those who recover are similarly discharged with the appropriate

support. Those who remain ill are usually transferred to a more traditional

health care facility or clinic. For caregivers as mentioned there is a

similarly stringent workflow that starts with putting on the PPE – donning –

through to how to safely perform even the most routine tasks like an IV and

then when your shift is complete how to safely remove your PPE – doffing. I’ll

save the mechanics of all that for a different time as well.

A

couple of good video links give you an even better picture of what goes on

inside an ETU. The first link is of the MSF unit at ELWA3 in Monrovia. The

second is from another Liberian ETU.

I’ve

included some stock pictures of ETUs. You’ll note an abundance of concertina

wire and snow fence. No locals call it snow fence but those of us lucky enough

to have seen snow or even ski (how I miss it this season) do. The snow fence

and concertina wire are to help indeed demand one follows the traffic patterns.

No getting in (or out) unless appropriate. No backtracking. No left when you

should go right. Some ETUs are refurbished buildings or clinics that already

existed in the middle of a town. Some are just tents, although really good

tents, and plywood buildings in the middle of the jungle. They all operate in a

very similar fashion. They have all been critical to the success to date. Even

those that have not seen a patient act as fire stations ready to jump on any

ember. There’s still both smoke and fire. The house isn’t burning down anymore

but there is still work to do. Lots of it. Don’t believe everything you see or

read on the news. In fact, burn your TV in the yard. I haven’t seen TV in

months. I don’t really miss it. Ah, that’s a lie. I miss the John Oliver show

like crazy. How am I ever going to catch up?

Note: The lyrics to Throw it all Away are

by Toad the Wet Sprocket

|

| Snow Fence |

|

| Island Clinic ETU |

So interesting to hear about all of this - nothing on Ebola is on the news anymore. Jess and the girls are so proud of all that you are doing. Just amazing and seems like all the steps you put into place a working with the number of new cases on the decline. Can't wait to have you back in Hawaii!!!!

ReplyDeleteGood post - could get a great mental image, even before looking at the photos. Goodonya for including lyrics from Toad The Wet Sprocket. Good band!

ReplyDeleteGodspeed.

Linda